Webcam shootout: D-Link DSB-C300 versus Logitech QuickCam Express

Review date: 27 May 2000. Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

It must be difficult to be a webcam designer. All your basic PC-connected video camera needs to have inside it is one little circuit board not much more than an inch square, on which sits the camera assembly. A fair few cameras have another board or two with support electronics, but they've only got about 50% more surface area all told. You can fold up all of the electronics for a basic webcam and pretty much fit it in a matchbox.

Because of this lack of practical constraints, PC cameras tend towards rather outrageous design. Umpteen variants on the "egg" and "eyeball" concepts have been made, not to mention various others that would probably be rejected by Starfleet Command for looking a bit too avant-garde.

D-Link have got into the act with their recently released DSB-C300. They've taken the easy way out on the styling front, and simply taken a curvy but not terribly exciting beige camera and changed the case material to see-through plastic. Hey, it works for me.

I played the C300 off against a slightly older contender in the webcam market, Logitech's popular QuickCam Express.

The two cameras have similar specifications. They both plug into a USB port, and come with Windows software (Windows 95/98 for the D-Link, Win95/98/2000 for the Logitech). They can both capture video and still images in various resolutions; up to 640 by 480 for the D-Link, up to 352 by 288 for the Logitech (for movies, at least - the highest still image resolution it can manage is 320 by 240).

They both have manual focus. They both have CMOS image sensors. And their US pricing's the same, too; $US50 retail for each.

Their Australian pricing isn't the same, though. The D-Link camera sells locally for $AU150; the Logitech's under $AU100.

There are some other differences as well. Actually, there are some rather big differences. As in, one of these cameras works properly and the other one doesn't.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Design

The QuickCam Express may look like your standard issue golf-ball cam, but it's a bit smarter than that. It mounts into its rubberised triangular base with a simple knurled plug that screws into the bottom of the camera. It's just a friction fit, but it works well enough.

If you unscrew the plug, though, the hole has a standard tripod-mount thread. The little round QuickCam looks a bit weird on a tripod, but it works fine. Presto, professional pans and accurate aiming are yours!

The D-Link has its clever points, too. For a start, it's got a button on the top that activates its capture software the first time you press it and takes a still picture the second time you press it. Logitech have cameras with buttons, but the Express isn't one of them.

The D-Link's plinth has a shiny metal plate in it for weight, and a sticky rubber base; the camera's therefore stable in pretty much any orientation, as long as the cable's weight doesn't yank it over.

You can easily pop the C300 out of the plinth and hand-hold it, if you like. There's no tripod mount, though.

The manual focus on each camera works the same way - a plastic collar that turns the lens. As with many cheap teeny-cameras, the focus thread and the lens mount thread are one and the same. Screw the lens in and you're headed towards infinity focus; unscrew it and you're headed towards the close-up setting.

There's only actually a few turns of the lens of useful focus, and the QuickCam's lens surround stops you going further. It lets you go far enough, though, that you can focus effectively on things only a few millimetres away from the camera.

The focus ring on the C300, on the other hand, is too tight, and has no proper end stops - it just gets harder and harder to turn at the extremes. This makes it impossible to tell when you've tightened the lens too much, and it's thoroughly possible to crank the lens right down and get it stuck. I did, and had to dismantle the camera to grab the lens barrel with pliers and free it.

Oh well, a chance to photograph the camera's innards.

I must say, see-through cases are a nice feature when you need to see where the little clips that hold the thing together are.

The Logitech camera, by the way, is held together by only one screw, and contains only one circuit board...

...hence its compactness. You're not likely to have to take it to bits, though, because you can't over-tighten its lens. The QuickCam's focus ring end stops are generously far out beyond the useful focus range, but they're still well before the jam-the-lens or unscrew-it-completely points.

Setting up

Plugging in these cameras is easy as pie, of course, because they're USB. No need to turn the computer off; just stick the plug in the socket.

Neither of these cameras comes with a tremendously long cable. If you want to be able to take pictures of things a bit further from your computer, a USB extension lead will give you another couple of metres of freedom. The maximum cable length allowed by the USB spec for high speed devices like cameras is five metres.

Neither camera has a microphone built in, but the C300 comes with a separate mike, again in a clear plastic case. This mike can slot into a cradle with a stick-on back, meant to be attached to your monitor, or you can remove it from the cradle and clip it onto your lapel. It plugs into the microphone input on your sound card.

If you don't have a mike to use with the Logitech camera, you're looking at no more than $AU15 or so to get one with the same features as the D-Link.

Of course, you can take all the still pictures and shoot all the silent video you like with no mike at all.

Dadaists may also enjoy running video-phone software and communicating with others by means of charades.

Software

The Logitech driver installation is easy. After the driver's set up, you install the QuickCam software, which lets you easily change camera settings, grab still or moving images, and export pictures and movies to e-mail and other programs.

Choose the "Custom" option in the QuickCam Express setup and you get to customise... where you want the software installed. Then the hands-off installation rips on as usual, doing an excellent imitation of those awful installers that trample DirectX and Media Player and who knows what else with older versions. Fortunately, this doesn't actually seem to be what's happening; I didn't need to reinstall anything afterwards.

The QuickCam package is training-wheels software that can't really be taken out of beginner mode, but it works well enough.

There's a TWAIN driver for the QuickCam, too, that lets more serious users grab frames without having to run the cutesy utility.

TWAIN stands for "Tool (or maybe Technology) Without An Interesting Name". Well, maybe not officially, but if the people that ought to have named it better can't think of what the name stands for, yet still insist on making it all-caps, they deserve whatever happens to 'em.

A TWAIN driver is a simple, standardised way for graphics programs to grab images from cameras, scanners or anything else, without the graphics program needing to know anything about the image source.

The D-Link software installation, in contrast, has some imperfections that are presumably evidence of its handcrafted nature.

The driver and basic software for the C300 come on a floppy disk. The installation process is simple enough, but it doesn't seem to be quite right for this camera. It asks you which port the camera's connected to - and lists only serial and parallel ports. I said it was a serial camera and rebooted when Windows said, as usual, that it needed to; lo, the camera worked. And there's even a TWAIN driver, which works quite well. The rest of the D-Link's driver software is rather primitive.

The D-Link capture program is a three year old utility called AMCAP. The Quick Installation Guide that comes with the camera tells you you're going to have to separately install something called Vidcap.exe, and goes on to tell you about various handy options you can set; AMCAP is something like the fabled Vidcap, but it's not the same thing, and nothing called Vidcap is included.

You do, however, get a CD-ROM containing MGI VideoWave SE for video editing, and MGI PhotoSuite SE for still image manipulation. "SE", as always, stands for "Skinflint Edition"; you don't get the full package features with these bundle-ware versions of the software. But they're not bad, for a cheap package like this.

You also get SmithMicro's Internet CommSuite, an Internet video-phone package with a few frills, none very exciting.

For actually grabbing video, though, all you get is AMCAP. And it's a pain.

Using them

All webcams have some inherent useability problems. If the camera's just sitting on a monitor, as many are, then it's easy to manipulate it and watch the preview at the same time. If you're trying to frame and focus a shot of some object, though, it can be hard to get it all together while you peer at the preview window on the monitor.

And grabbing still frames from webcams that have a shutter button can be annoying, because the act of pressing the button can move the camera enough that the picture ends up blurred.

Webcams are also, by definition, tethered to a computer. You're not going to go on the road with one, unless it's plugged into a laptop. You can, at least, extend your range a bit with these USB webcams by using a USB extension cable.

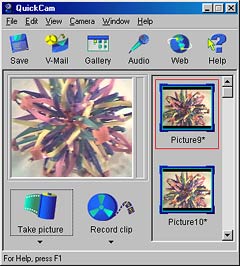

Using the QuickCam Express, within these limitations, is easy enough. Run the software, tell it to grab a still or video, export to files or other programs or e-mail or whatever. It's a good system for home users, with a standard built-in Gallery feature to keep things somewhat organised. It's simple to access the setup options, play with the camera settings, select the quality for e-mail videos and so on.

You can't change the video encoder the QuickCam software uses, and the still image resolution can't be set higher than 320 by 240, but this isn't a camera for power users.

The D-Link software's more annoying.

Fiddling with the C300's settings strengthened my suspicion that AMCAP just isn't meant for this camera.

There are lots of things you can change, but most of them are greyed out, or the setting only actually changes over some subsection of the total range of the slider control, or nothing at all seems to happen.

Fortunately, the default settings produce not-so-bad looking video.

Unfortunately, the still image quality is poor. And there doesn't seem to be much you can do about it.

By default, the C300's images tend to be badly washed out, like this:

This is a very colourful object, but you wouldn't know it to look at this picture.

Here's the Logitech's opinion of the same subject:

Not award-winningly wonderful, I grant you, but more like the real thing. Which, in case you're wondering, actually looks like this:

This shot's taken with my Olympus C-2500L digital still camera (compared and contrasted with Sony's DSC-F505 here), in the same well-lit-room-at-night conditions as the webcam pictures.

Click the image for a 320 pixel wide version. The original was at the C-2500L's full resolution, which is 1712 by 1368.

The Olympus also has a flash. A good one. It makes a difference.

This is, of course, a totally unfair comparison. The C-2500L is 20 times the price of a basic webcam, and it can't even do video.

But, nonetheless, it pays to realise that even if you're just getting pictures for a Web site and 320 by 240 is perfectly adequate, an entry-level webcam is not going to give you results anything like as good as those from a proper digital still camera. You can get decent digital still cameras from $AU500 or so, and if you need good quality instant digital pictures, you're going to have to.

Twiddling the D-Link's image quality settings didn't help its performance much at all. I could make dark, washed-out images, or light, washed-out images.

This is about the best I managed from the indoor subject:

You can help things a bit with post-processing...

...but you can't put back what was never there.

It's not a lighting issue. Daytime still pictures with the D-Link are just as anaemic:

The detail in this 640 by 480 image (click for the full version) is actually rather good, although the little lens creates some rather nasty distortion in the corners. But the colour's crummy.

The C300's video results in well-lit conditions are better than its still pictures, for some reason; here's a frame grab from a video clip taken with the C300 looking out of the same window:

And here's the QuickCam's view from the same place:

Lousy detail (tweaking of the gain control would help), but much more colour.

And, again, here's what the scene really looks like, courtesy of the C-2500L.

If the D-Link camera couldn't do 640 by 480, its crummy colour would make it a dead loss for stills. As it is, it's borderline. I don't think it's actually the camera's fault; its preview image is fine, and its video capture is not bad. But without better software, that doesn't do whatever the stock driver does, the hardware doesn't get to show its stuff.

Incidentally, using the TWAIN driver to grab still frames from the C300 doesn't give better results.

The marketing rainbow

D-Link accidentally specify the DSB-C300 as being good for "64 million colours".

Which it ain't.

I'm pretty sure it's just a 16 bit colour device, which means exactly 65,536 (two to the power of 16) colours come out of the camera. This is the same number of colours your computer can display if you set it to 16 bit colour (or, in Apple's don't-frighten-the-users parlance, "thousands of colours").

16 bit colour is often referred to as "64 thousand colours" by people who haven't quite come to terms with the fact that binary works in powers of two, not powers of ten.

The normal steps up from 16 bit colour are 24 bit and 32 bit, with 16,777,216 and 4,294,967,296 possible colours, respectively.

Grab still images with the C300 and you'll save simple uncompressed 24 bit BMP images with more colours than that, but not a lot more; they generally don't beat 70,000 unique colours. I think the software post-processing accounts for the extra colours above the 16 bit "colour gamut", but I could be wrong.

In any case, 64 million is a technically ridiculous claim.

The difference between 16 bit and 24 bit can be quite obvious on images with smooth colour gradients. 16 bit colour assigns five bits each to the red and blue channels and six bits to the green - in most signals, green comprises about two-thirds of the total image data; that's just how the colour balance of things tends to work out.

This means 16 bit gives you only 32 (two to the power of five) possible intensity levels for the red and blue components of the image, and only 64 (two to the power of six) levels for green. It's thus hard to get a smooth gradient using 16 bit colour; if it's dithered (using alternating pixels of different colours to create the impression of an intermediate colour) the difference can be hard to pick, but video capture systems like this do not have the power to do dithering on the fly.

Hence, "banding"; the creation of noticeable bands of colour where there should be a smooth gradient.

If you've got 24 bit colour, that's eight bits per channel; 256 steps for each. In 32 bit colour it's 10, 10 and 12 bits for red, blue and green respectively; 1024, 1024 and 4096 steps.

There's no perceptible difference between 24 and 32 bit colour images - canonically, 256 intensity levels is all you need for photographic quality; normal greyscale images are thus only eight bit. But if you're manipulating an image and/or mixing images together, the much larger colour gamut available from 32 (and even higher) bit images means that even when your manipulations result in only a small slice of the original gamut surviving to the final image, you still get a smooth, tasty result.

The DSB-C300 could deliver 64 million colours, if D-Link had invented 26 bit colour. Well, it'd be 67,108,864 colours, actually, but if 65536 equals sixty-four thousand, then 67,108,864 by the same logic equals sixty-four million.

The QuickCam doesn't deliver any more colours than the D-Link does - a few tens of thousands, even from multicoloured subjects, is still the order of the day. But its still shots contain rather more accurate colours, which is what matters.

Incidentally, my C-2500L shots of multicoloured subjects generally contain about half a million distinct colours, from its entirely genuine 24 bit palette.

Frame rates

For decent video quality, you need a reasonable frame rate. Anything above 20 frames per second will look smooth.

The C300 is specified by D-Link as being able to do 640 by 480 video capture at a respectable 18 frames per second, but it won't on most PCs. Dropping the capture colour depth to 16 bit - which you might as well, given that that's all the camera delivers anyway - allowed it to struggle up to about seven frames per second on the 667MHz Pentium III test machine.

The reason for this is simple enough. Hard drive speed. Most drives just aren't fast enough for high resolution digital video, unless you compress it on the fly, and neither of these cameras does. Cheap Webcams pretty much never do much in the way of compression while they're capturing, because it just uses up too much CPU power, even on current computers. They may compress the data later, but not as they capture it, and after-the-fact compression's no good to you if you can't get the video onto your drive in the first place.

Serious video capture systems have real time compression hardware built in, which gets around this problem.

At 640 by 480 in 16 bit colour, there's 600 kilobytes of raw image data per frame. Seven frames per second, therefore, is about four megabytes per second, which is as much as the cheap 5200RPM drive in the test machine can take.

At 320 by 240, even in 24 bit colour (three bytes per pixel), you're only talking 225 kilobytes per frame. 30 frame per second uncompressed 320 by 240 16 bit video therefore requires about the same drive speed as seven frame per second 640 by 480; both cameras can, indeed, manage nice smooth 30 frame per second capture operation at this resolution. If something starts flogging the same drive you're capturing to, you'll drop frames, but if nothing interrupts the capture operation, you'll be fine.

You'll be making a rather big file, of course, but today's cheap multi-gigabyte drives make this a lot less of a concern than it used to be.

You might be able to get worthwhile 640 by 480 capture speeds out of the D-Link camera with a faster hard drive - current super-high-capacity drives have higher transfer rates, and 7200 and even 10,000RPM drives are becoming more common. But don't bet on it.

The D-Link AMCAP software has compression options in the rudimentary video capture setup window, but they're greyed out. You can move a compression slider, but nothing changes.

The data rate of video from the QuickCam Express is a bit lower for a given setting, because it captures in only 12 bit colour. I think it must be picking its 12 bit palette from a larger colour gamut, though, because there's no more banding in its output than in that from the C300.

Overall

Neither of these cameras really shoots good video or stills, but never mind the quality, feel the price. You can't expect to get a particularly impressive colour image sensor for this kind of money, and neither are you going to see super-clear, low-distortion optics.

The D-Link's 640 by 480 maximum capture resolution helps it a lot, if you can tolerate its washed-out still image colour and confusing driver software. The QuickCam Express has a better driver, but doesn't come with bundled paint or video editing software. Not that you're likely to do a whole lot of editing of low-res webcam video anyway, but it's still nice to have.

If these cameras cost the same - as they do, in the USA - then I'd pick the QuickCam if I wanted something foolproof, and the DSB-C300 if I wanted something that could take reasonably high resolution shots, and didn't mind them being rather grey.

In Australia, though, D-Link gear seems to carry an inexplicable price premium. For 50% more dollars than the QuickCam, the D-Link's not a very attractive prospect. It could still be worthwhile if its driver worked properly. But it doesn't. So it isn't.

For not much more than the price of the D-Link camera, you can get a classier Logitech unit, like the QuickCam Home I review here which currently sells for $AU180. Built-in microphone, USB connection, same friendly software, somewhat better image sensor. By pricing themselves out of the bargain-basement end of the market, D-Link have turned a reasonable product into a crummy one.

Buy a webcam!

Readers from Australia or New Zealand can purchase webcams from

Aus PC Market.

Click

here!

(if you're NOT in Australia or New Zealand,

Aus PC Market won't deliver to you. If you're in the USA, try a price search

at

DealTime!)