Benq VP150X video projector

(and how to find a cheaper alternative)

Review date: 23 March 2002. Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

It's hard not to love video projectors.

There's unmistakable attractiveness in a gadget the size of a phone book - or, at worst, the size of a suitcase - that can cover a whole wall with your TV, movie or computer image.

Projectors are great for home theatre, and for big screen sports TV, and for jaw-droppingly enormous delivery of appropriate video games. And for subversive public media events.

I'm told that people use them for business presentations, as well. But this is a family publication. Let's speak no more of such things.

Head Mounted Displays are getting better and better, and will probably be a perfectly sensible option for solo virtual-big-screen applications in the quite near future.

They're no good if you want more than one person to be able to see the display at once, though. For group viewing, the only alternative to a video projector is a big-screen TV.

Probably a very big-screen TV.

Now, I don't know about you, but I don't want to see cheerful news stories on my whole darn wall. I certainly don't want to turn over an armchair's worth of floor space to a monstrous black box. And pay a fortune to buy it. And have to hire piano removalists if I ever want to shift the thing somewhere else.

Get a projector and these problems go away. Use a TV (or computer monitor...) of modest dimensions for normal watching, and the projector for big screen events.

There are lots of projectors available, many of them accept input from all popular home entertainment video gear (VCR, DVD player, game console, PC...), and even the ones that aren't described as portable are generally a lot easier to shift around than even a medium-sized TV. Portable and "ultraportable" projectors can be carried by the weediest of home theatre enthusiasts, and easily stowed when you're not using them.

All you need is enough money to buy one.

Here's an excellent example of exactly the kind of general purpose small projector that lots of people would like to own, but can't afford. It's the VP150X, from Benq.

Benq, in case you were wondering, is not just the sound made by a sparrow flying into a milk bottle. It's also the new name for Acer Communications and Multimedia, who retain their "acercm" domain names here in Australia and elsewhere, but have realigned their dynamic cross-media network empowerment by changing their name and turning purple.

There's some reason for this; Acer are a computer gear company, and the-artist-now-known-as-Benq is the sub-entity responsible for... well, everything that isn't computer gear. But then again, Benq apparently want people to capitalise the Q in their name, so it's hard to have a lot of sympathy.

Peculiar names aside, the VP150X is a quality piece of gear. As you'd bleeding well want it to be, since it lists for $AU9,299.

This isn't actually particularly expensive for projector of this type - lots of portable business projectors list for more than $US5000. But it's still rather more than you're likely to want to spend.

Fortunately, there are alternatives. There are lots of sources for cheaper video projectors than this. Auction sites. Classified ads. Trade-in and ex-rental units at A/V places.

Cheap projectors - which is to say, units costing from around $AU1000 to around $AU2000 - used to be pretty ghastly, if you could find them at all. But the march of technology's bringing some perfectly OK hardware down into a more sane price bracket.

So let's have a look at the VP150X, see what it gives you for its substantial price, and also see what compromises you'll have to make if you scout around for something cheaper instead.

The VP150X is a true ultraportable projector; it weighs 3.6 kilograms (eight pounds), and it's 240mm wide by 99mm high by 325mm deep. And it's got a pop-out handle on the side. There are a few cheap second hand ultraportable projectors around, but you probably don't want one. Go for something bigger and you'll get better specs for the money.

The VP150X gives you a 1024 by 768, 4:3 aspect ratio display. Almost all projectors are 4:3, like almost all televisions and computer monitors; it's not the ideal solution if you want to display widescreen video, but it'll do.

You're not going to find a 16:9 projector, even second hand, for much less than the price of the VP150X; the 1366 by 768 resolution 16:9 Sony VPLVW10HT that I reviewed here is now more than two years old and has been superseded, but still goes for $US5000 or more from many dealers.

The VP150X, of course, works with 16:9 widescreen aspect ratio video as well as 4:3. But it does that the same way as every other 4:3 device, by "letterboxing" out the top and bottom of the 4:3 display area. In 16:9 mode, you get only 1024 by 576 resolution.

That actually neatly matches the number of lines in Standard Definition PAL TV signals, and it's quite a lot higher than the real vertical resolution of letterboxed video-tape movies. But if you're running from higher resolution input - anything better than widescreen Standard Definition PAL, like for instance anamorphic widescreen DVD movies delivered via RGB component video - you'll lose some sharpness.

If you buy a cheap projector, you're probably not going to get 1024 by 768.

800 by 600 projectors are pretty common on the second hand market now; they're a good general purpose choice, and deliver quite acceptable video playback quality as well as having enough pixels for reasonably impressive computer graphics. But, obviously, they're even less suitable for high definition widescreen applications, and cheaper 640 by 480 units are worse still.

Sharpness is a problem for LCD projectors in another way. They've got too much of it. Their pixels don't run into each other - they're separated by a black gridwork, which can be quite noticeable on old 640 by 480 models. This isn't really a problem for projecting computer graphics, but it doesn't look great for video sources.

The "flyscreen" on 1024 by 768 LCD projectors like this little Benq isn't very noticeable. The usual way to make it less offensive on any projector is just to slightly unfocus the image. Which ain't elegant, but it works.

The VP150X has 24 bit colour capability, like every other current digital projector, and most used models too. Suspiciously cheap digital projectors (and LCD monitors), however, may have only 15 or 16 bit colour. That means that smooth colour gradations will show banding, the same way as they do if you set your colour depth to 15 or 16 bit on your PC.

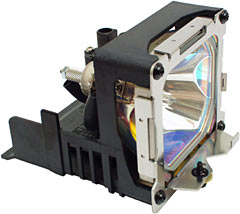

Here's the VP150X's lamp assembly. It uses a 150 watt Matsushita HS150AR11-21, which your local Matsushita/Panasonic distributors may know about, but which certainly doesn't seem to be listed on any of that company's multitudinous Web sites. Finding replacement lamps shouldn't be an issue, though - well, not until this projector's old and crusty, anyway. You can expect to pay around $US350/$AU700 for a lamp like this.

Replacement lamps for old projectors can be a serious hidden cost - partly because they may be hard to find and even more expensive than lamps for new projectors, and partly because they may not last very long.

The VP150X's lamp, like most other current "Ultra High Efficiency" metal vapour short arc models, has a 2000 hour service life. The projector enforces this life by warning you when its built-in lamp timer hits 1950 and 1979 hours; it refuses to work after 2000.

It's possible to just reset the lamp timer and keep on trucking until the lamp actually dies - maybe it'll explode, just like old fashioned short-arc lamps used to do now and then, but I wouldn't lie awake at night worrying about that. It may be dim enough after 2000 hours that you'll want to change it anyway, though; UHE lamp brightness falls away as the bulb ages.

Even if you use a projector for five hours a night, though - and you probably won't - then 2000 hour lamp life is more than 13 months of use. That's a pretty lengthy amortisation period. About 35 Australian cents per hour of viewing ain't bad at all.

The lamp, by the way, has its light output evened out by clever optics, starting with this "fly-eye" lens array. Which I thought was pretty enough to be worth photographing.

The upshot of this is that the VP150X, despite its smallness, has good brightness uniformity - the picture isn't significantly brighter in the middle than it is around the edges. The older and cheaper a projector is, the more likely it is to fall short in this department.

The VP150X manages a very impressive 1800 ANSI lumen brightness. That means you can get a viewable image out of it even in a well lit room, as long as you keep the image size small; it also means the projector can throw a really big picture in a dimly lit room, as long as you've got enough space to get the projector far enough back from the screen.

Old, cheap projectors will be dimmer than the VP150X, and probably by a wide margin. 600 lumens is a good output level for a smallish, cheapish projector a couple of years old.

The down side of high brightness is that it makes everything bright, including the parts of the image you want to be black. Digital projectors, particularly LCD models, are incapable of blocking all of the light from their super-bright lamps for the parts of the picture that're meant to be black. Newer models like the VP150X do better, but they're still not great.

You can tell how well a projector does in this area by looking at the "contrast ratio", which tells you the ratio between the brightest and dimmest output the projector can manage.

Well, that's what it's meant to tell you, anyway. Unfortunately, contrast ratio is hard enough to measure that there's no agreement among projector makers on what standard to actually use.

Benq claim a 400:1 contrast ratio for the VP150X. That seems to be a reasonable basis for comparison between this and most other projectors, so far as I can see. And it's not a bad figure, though it's well down on what the current crop of (rather more expensive) serious home theatre projectors can manage.

For viewing in un-darkened rooms, contrast ratio isn't nearly as important as brightness, because the ambient light will swamp all of the darker tones anyway. If you want to use your projector in a darkened room, though, a unit with a lousy contrast ratio will give you a much more washed-out looking image than you'd get from an ordinary TV.

This isn't as bad as you might think - you can get used to rather grey blacks surprisingly quickly. But, for some program material, a low contrast ratio means you just won't be able to see the picture properly.

As a general rule of thumb, bright scenes look fine with anything better than about 150:1 contrast ratio. For general video, 300:1 is OK. For dark scenes - and some feature films are riddled with dark scenes - you need something like 1000:1 to see everything that's in the source material. Cheaper projectors commonly manage only 200 or 300:1.

You can improve apparent contrast ratio, and reduce washing out from ambient light, by using the right sort of screen with your projector.

Many projectors at parties end up pointed at a white wall or an old slide projector screen. That gives you great brightness, and you can't beat those options for price. You can do better, though.

Bespoke screens made of exotic fabrics can cost more than $US1000 for a 100 inch diagonal 16 by 9 rectangle. You get something for all that money; fancier screen materials have optical coatings that eat light coming at them from the sides (where the projector isn't), yet are still good at diffusely reflecting light coming at them from the front (where the projector is). If your budget doesn't stretch that far, though, a plain grey finish with no special optical properties will still reject ambient light better than any white screen. If you've got a pretty recent "light cannon" projector, the lower brightness of a grey screen isn't going to be a problem.

Home theatre enthusiasts on shoestring budgets often make their own screens. White painter's canvas on a frame will do just fine, and you can use ordinary hardware-store grey paint if you want to knock down ambient light problems a bit. If you're not that handy, second hand grey slide projector screens are often excellent value.

The VP150X's lens has separate manual zoom and focus controls. Every projector has focus, but cheap projectors don't necessarily have zoom. Without zoom, the size of the image the projector can throw is directly determined by the distance it's sitting from the screen - which means you may end up having to set it up somewhere inconvenient, or find that you just can't get the picture as big as you want.

The VP150X only has 1.3X zoom, but that's considerably better than nothing. You can set this projector up from 1.64 metres to 12.55 metres from a screen (any further or closer and you'll run out of focus range), and its 4:3 diagonal image size at those two extremes is 40 and 300 inches at full wide angle, and 30.76 and 230.76 inches at full zoom. It's bright enough that the 300 inch picture's actually good enough for something, too.

For a baby projector, the VP150X has a lot of inputs. And some pass-through outputs, too.

From left to right, we've got 14 pin VGA (RGBHV) input and monitor passthrough, and 1/8th inch stereo audio input and passthrough. You probably won't be wanting to use the VP150X's little built-in speakers for anything but business presentations, but it doesn't hurt to have them. Then there are the two mouse-emulation connectors (one USB, one combination connector that accepts different cables for serial, PS/2 and Apple Desktop Bus). And, on the right, there are three RCA connectors for stereo audio and composite video, plus a mini-DIN connector for S-Video (Y/C) input. There's no pro video component input (Y/Pb/Pr), but you probably don't need that anyway.

Input selection on the VP150X works simply enough. You connect the cable(s) and, by default, the projector auto-detects whatever's sending it a signal. You can also switch inputs manually using an on-screen display.

Through the VGA input, the VP150X accepts anything from 640 by 350 (EGA resolution, in case you care) to 1280 by 1024 (which is referred to as SXGA by people who think it's actually a real standard of some sort). You should be able to feed the VP150X any computer-output resolution within this range and have it work. Including, by the way, standard VGA text mode, which is 720 by 400.

If you use 1280 by 1024 (which will be scaled down to fit the 1024 by 768 panel resolution), you can't use a refresh rate above 60Hz. Various refresh rates up to 85Hz are supported for lower resolutions. This is because the electronics that digital projectors use to convert analogue VGA input into a digital bitmap image have their limits; digital projectors don't actually have a refresh rate in the cathode-ray-tube sense, so low refresh rate input won't flicker. Old cheap projectors won't necessarily accept VGA input above their physical pixel resolution, and may have tighter refresh rate restrictions as well.

None of this is a big deal, as long as you set your computer's resolution and refresh rate appropriately before hooking it up to the projector. If you forget to do so, though, you'll be viewing a signal-out-of-range screen.

Through the composite and S-Video inputs, the VP150X can handle pretty much every TV standard - NTSC, PAL (including the South American PAL-M and PAL-N flavours), and SECAM. Your average cheapo-projector may or may not be happy with video formats other than the one used in your country. And all bets are off if it's a grey import unit from some other country. You have to check that a projector can accept the video you want to throw at it.

Many current DVD players and VCRs can output a PAL signal when playing NTSC movies (or vice versa), though, which gets around this problem.

Suspiciously cheap projectors commonly lack VGA input; lots of cheap projectors only take composite and, usually, Y/C input. If you've got a PC with TV output then you can plug it in that way, but if you're expecting better than 640 by 480 resolution from that, you're going to be disappointed.

There are a few projectors which only give you computer input as standard - like the older Acer model I review here, for instance. That one's got an optional clip-on composite-and-Y/C module, which didn't come with the unit I got for review.

The buttons on the top of the VP150X are coated with finest photographer-reflecting chrome.

There's an "i-key" button there, which auto-sets the projector to match the input signal. It's the same idea as the one-touch setup buttons on LCD monitors, basically; press one button and the projector picks the image width and height, and sets its white level to the maximum input signal strength, too. Projectors without such luxuries generally aren't difficult to set up, though; setting up old three-gun CRT projectors can be quite an adventure, but single-lens digital units are all quite straightforward.

If you buy a cheap projector, don't expect to get a remote control this fancy, if you get one at all.

Acer - sorry, Benq - like making these double-barrelled remotes. One hole in the front has the usual infra-red LED in it, and the other one's for a laser pointer. Apart from that, and general setup controls, the remote's main feature is that you can use it for proportional mouse control, moving the pointer with the pad in the middle and clicking and dragging with buttons provided for those purposes. You just connect the projector to your computer with one of the provided cables; you don't need a special driver.

Mouse emulation's a handy thing for a business projector, and nifty if you want to control remote control Winamp visualisations at a party or something, but it's not a feature that most people need. If you must have cordless control, after all, cordless mouse and keyboard sets (like the one I reviewed here recently, for instance) can be had pretty cheaply.

Among the other handy-for-business features that the VP150X has and that many projector buyers don't care much about are freeze-frame, digital zoom (you can scroll around the image while you're zoomed in with the mouse-pad), and a screen blank button. The blank button doesn't turn the lamp off; it just changes the image to black. Actually turning the lamp off requires a one minute cool-down delay, and that's what happens when you turn the projector off. Other digital projectors do this, too, and most of them won't let you turn the lamp back on again until its cooling cycle is over. Turning the projector off at the wall before it's cooled its lamp is not a good idea.

Modern UHE lamps warm up quickly, so you don't have to wait long to use the projector after turning it on. Older projectors may have considerable startup delays.

The Benq remote lets you access all of the projector setup features, so you don't have to pore over the top buttons in the dark. You can fiddle with contrast and brightness, and with colour balance and tint and sharpness (sharpness is a video-in option only).

All of this stuff is normal; it's hard to find a projector that won't let you fool with its image in all of these ways. Different projectors have different ranges of adjustment - a projector with a lousy contrast ratio can't be made better no matter how much setting-tweaking you do - but the basic adjustments are much the same for everything with a given set of inputs.

The VP150X also has keystone correction, to correct for the pie-slice shape the projected image will have when the projector's aim-line isn't perpendicular to its screen. But the keystone correction is just digital, as it is with most projectors; it straightens the edges of the image by squishing the top of the image digitally, using fewer and fewer pixels on the higher lines. This creates noticeable distortion in computer graphics, and throws away some resolution.

There are better ways to deal with this problem.

One, of course, is just to aim the projector pretty much straight at the screen. This requires it to be level with the middle of the image it's throwing, though, which may not be physically possible.

Some projectors have optical keystone correction; their lens basically works like a shifting lens for a camera. But if you can't afford the VP150X, I strongly doubt you'll be able to afford one of those.

The budget solution to keystoning is to project onto a screen that has tilt adjustment. The projector aims upwards; the screen tilts towards it. Most stand-alone screens have a little notched rack at the top, or some similar widget that lets you move the top edge of the screen forward relative to the bottom edge. That's exactly what you want to do to get rid of keystoning without using digital correction and losing some of the pixels you paid for.

With a tilted screen, of course, a person looking horizontally at the middle of the screen will see the top of it as being bigger than the bottom. But since viewers are usually looking up at a big screen, at much the same angle as the projector's aim-line, this isn't a problem.

One thing that a lot of small projectors don't have, but the VP150X does, is image flipping. If all you want is a normal front-projection setup with the projector sitting on a table, then you don't need to be able to flip the image. But if you want to do rear projection, then you have to flip the image horizontally to keep everything the right way around. And if you want to ceiling-mount the projector upside down (so that its keystone correction still works and you can reach its buttons), you'll need to vertically flip the image for rear projection, and vertically and horizontally flip it for front projection.

The VP150X can do all of this stuff. Some other projectors can do some of it. Cheap projectors commonly can't do any of it. If you're just doing normal front projection then it doesn't matter; if you aren't, then it does.

If you want to ceiling mount the VP150X and you don't want to do it with baling wire, you can get an optional kit that's alleged to make it easy. The only other optional extra for this projector is an "Objective Display Camera", which you can point at documents to let you use the VP150X like a really, really expensive overhead projector. Camera-equipped video projectors can, of course, project images of normal documents, not just transparencies. Whether that's worth paying 15 times as much money for the projector is left as an question for the reader.

For your giant slab of money, Benq at least give you an OK steal-me bag to carry the VP150X around in. Yes, the projector has a handle, but that's for carrying it from carpeted office to carpeted boardroom, not on the train.

Note: People who carry expensive gadgets around a lot often prefer to put them in luggage that's less attractive to thieves.

The Benq bag comes, as shown above, with a box full of cables in it.

You get a 14-to-14 pin VGA cable, with an adapter that lets you connect it to older Macintosh monitor outputs. There are also Apple Desktop Bus, PS/2 and serial mouse cables. And a three-connector RCA cable for regular stereo audio and composite video connections, plus a separate single RCA audio/video cable. And a USB cable, and an S-Video ("Y/C") mini-DIN cable.

There's also what Benq mystifyingly call a "General Cable", which unless I miscounted the cables in the box, is actually just a normal 1/8th inch stereo audio lead.

There's also a power cord - or, in the case of the projector I got for review, several of them, all with different plugs. The VP150X has a standard IEC socket on the back of it, and a multi-voltage power supply that'll work in from 100V to 240V countries. So if it doesn't come with the right lead for wherever you are, all you need is an IEC power lead that does fit in whatever sockets they use in Elbonia.

Like all digital video projectors, the VP150X is fan-cooled. Since digital projectors work by running a really bright, really hot lamp all the time and interrupting a large amount of its output with their image-creation hardware, they need quite serious cooling to avoid unsightly loss of magic smoke.

The VP150X fan is decently quiet - Benq rate it at "<40db", but don't specify at what distance. It shouldn't be a nuisance for all but the pickiest viewers of the quietest movies, and it doesn't have a side exhaust that'll barbecue the side of any viewers' heads, either. There's a removable foam dust protector over the top of it.

Cheap projectors are likely to be louder than the VP150X. Maybe much louder. They may have exhausts in annoying places. They may have badly clogged dust filters, or no filter at all; very small projectors often have inadequate filters, and careless users may just discard a filter when it gets clogged.

Replacing a filter isn't that hard, but getting dust out of a projector can be a different story. Theoretically, since it got in, it can get out again. In practice, pulling the projector apart and gingerly puffing away at image-path components with a rubber-bulb blower, and possibly only managing to move the specks around, is probably not the way you want to spend an afternoon.

Dust in the image path can give you bright specks on the picture, and you won't necessarily notice them if you view a well-focussed image in a room that isn't dimly lit. Red specks aren't likely to be noticeable at all unless they're really big; blue and green ones can be very annoying.

If you're buying a second-hand projector, you can check for coloured specks even in a quite brightly lit room, by deliberately unfocusing the image. Dust speck artefacts are usually fuzzy blotches when the image is properly focussed, but when the image is well out of focus one way or the other, dust specks may come into focus and be much more obvious, even when there's lots of ambient light.

Overall

Neat little projectors like the VP150X often end up being used for games and video nights, but only because people pinch them from the office on the weekend.

Normal people, however, can buy a quite good video projector these days, for around the price of a PC.

It's not hard to find specs for most models of projector on the Web. This saves you from trying to figure out whether the person selling the thing in the newspaper classifieds actually knows what a 14 pin D-sub connector is, and it also ought to let you easily find out the part number for a replacement lamp, so you can check with your local A/V places to see whether they're still available and not hilariously expensive.

Two grand Australian won't buy you the Perfect Home Theatre, but if you shop around a bit, it will get you a big-screen rig that'll look OK, be easy to set up at your own place or someone else's for movies or games or televised sports or what have you, and be easy to pack away when you don't want the room to be dominated by a wall-sized TV any more.

Would I like a VP150X? Sure I would. It's a fine product.

But there's better value to be found in the bargain bin.